My father was deep

by Denardo Coleman

Complete Liner Notes from Gatefold Booklet

My father was deep, meaning his way of thinking and intuition could not be tracked. But he always seemed to bring new insight, new logic to whatever he was contemplating. The sound of his horn reflected this depth, the depth of the emotion of the raw soul. His concepts so advanced, so intellectual, yet his expression so human, so direct. He created and spoke his own language. For some his music was too complicated, too abstract, nothing to grab on to, just too out there. For others it was utterly profound because it spoke directly to the brain and to the soul simultaneously. As he would say, “It’s about life. You can’t kill life.” He was obsessed with expressing life through sound. He went into its properties as scientists had explored genomes, discovering DNA. He called his science Harmolodic. Open thinking, equality, freedom, the pursuit of ideas, helping others all included. He would say, “It’s about being as human as possible.”

This project began on June 12, 2014 almost exactly a year before my father passed away. That day we had a big tribute concert celebrating him at Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. For all who were there, both performing and attending, it was magical, a spiritual experience. A Who’s Who of artists across all genres were there paying homage, and just freely letting that Ornette energy flow through them.

I was preparing this project for release when my father started experiencing difficulty. His body finally gave way on June 11, 2015 after a brief stay in the hospital. Shortly thereafter, we held a memorial at The Riverside Church here in New York. I had never been to a service where people emerged utterly joyous and smiling. Again, that Ornette energy, so unique and profound, had lifted the room. Defying category, that energy, both down home and highly advanced, is an Ornette kind of authenticity. The service made people feel really good, this window into such a unique being. The words spoken and music played, all from the heart, completed what grew into a yearlong celebration of my father. That is why I decided to put it all together and present it all together here.

I came to New York with my mother in the fall of 1959, when I was three years old. We were coming in from Los Angeles. New York was freezing. We stayed at the Van Rensselaer Hotel on East 11th Street. (Some things you don’t forget.) We were here because my father was opening at The Five Spot. Of course, I had no idea of the controversy his music was generating. I was equally unaware of it when he and I started playing music together in the garage back in Los Angeles, a few years later. And I was still oblivious to it as a 10-year-old in 1966, when I went with him and Charlie Haden to Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in New Jersey to make a trio record for Blue Note.

But in the space of those seven years, my father had become the talk of the jazz world. He retired, came out of retirement, produced his own concert at Town Hall, began composing for “classical” instrumentation, and recorded and released 12 albums. He devised challenging, provocative titles like, “Tomorrow Is The Question,” Change of the Century,” “The Shape of Jazz to Come,” and “Free Jazz.”

With album titles like that, you would expect to find someone driven by attention, a self-promoter. But to the contrary, my father was an utterly down to earth, humble person. This is why I had no idea of all of the attention he was getting. He just wasn’t driven by notoriety or fame. He was on a mission to be who he was. On a mission to develop his own ideas about sound and about music. At the same time, reflecting generosity and humanity.

My father’s “guys” in those years were Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, Billy Higgins, Ed Blackwell, Charles “Diddy” Moffett, David Izenson, Bobby Bradford, and Dewey Redman. By that, I mean I know what they had to go through. The endless commitment to rehearse and explore the properties of sound, sometimes for months without a paying job in sight. The mission, as it turned out, was a spiritual one. Unlocking the energies in music that included healing and higher awareness. Not complicated to be complicated, but sometimes to truly reach the depths of understanding you have to explore, layer by layer, going deeper and deeper. Sometimes people can feel it and follow, sometimes they can’t. No reflection on anything.

I witnessed him doing this month after month, year after year, manuscript book after manuscript book. He would constantly buy these music notebooks, often at a specialty shop near Carnegie Hall. Then fill them up book after book. But these were the guys who went on the journey and into battle with Ornette. I climbed into “the empty foxhole” with them (to quote our LP title,) and was surrounded and protected by all of my uncles on that recording date in 1966. And here we are, 50 years later, still carrying on.

Later on, Ornette’s people would be James Blood Ulmer, Bern Nix, Jamaaladeen Tacuma, Ronald Shannon Jackson, Charlie Ellerbe, Al Macdowell, Kamal Sabir, Calvin Weston, Chris Walker Dave Bryant, Badal Roy, Chris Rosenberg, Brad Jones, Kenny Wessel, Charnett Moffett, Joachim Kuhn, Tony Falanga, and Ms. Geri Allen. The same for everyone, The University of Ornette! He was so prolific that at one period, he wrote new music for each concert. If we had a run of eight shows coming up, we probably played 60 new tunes and five old ones and that’s how it went.

I spent a long time playing with my father, recording, traveling, managing, fighting, endlessly laughing, and going from one exhilarating experience to another. You had to be immersed in Ornette World to realize this wasn’t merely his music — this was how he thought, how he lived. Back in the day we would go real late at night to his favorite Chinese restaurant, at 21 Mott Street, and he would order ten dishes even though there were only four of us. He liked to have lots of different dishes to taste and then to mix together. That’s right, even our dinners were Harmolodic. And forget about giving away the extra food to a homeless person – Dad would see a homeless person on the way home and invite him to sleep at his house.

In the late ’60’s he bought the third floor and ground floor loft space at 131 Prince Street, in what was to become Soho. He called the ground floor Artist House. He put on his own performances there and let other artists put on their own performances free of charge. He put on exhibits of painters he brought in from Africa and other places. It was the sort of open and encouraging environment reflective of his spirit. It went on until the mid-70’s. Then Soho became Soho and the artists were out.

I started managing my father’s career in the 80’s, in my mid-20s. I had been out of college for a few years and playing with him. My father would enjoy a great run of activity and success and then shut it all down for a while, frustrated yet again by the music business. He always felt taken advantage of by managers, promoters, record companies. Finally, I couldn’t sit by and watch the endless cycle of boom and bust any longer. One day I just said, “Let me manage you. You won’t have to stop and wonder if you are being ripped off.” He said okay, and for the next 30 years we did our best to turn ideas into projects.

His journey, which began in the 1950’s, was hard, not easy at all. The music business was out of sync with him, and he was out of sync with it. We had terrific battles as I was trying to create some kind of link. He had already turned the world on its head long before I came along. But with a little more stability, we could do more and we did. A lot. His own multi-day festivals across the world, a record label, recording studio, partnering with the Caravan of Dreams Art Center in Ft. Worth, commissions, symphony performances — many, many projects. Then came the numerous awards and honorary degrees — all the result of him being doggedly stubborn, fiercely fighting to be independent and an example of artistic freedom.

Playing with my father was a fairly endless series of highlights, but what I think I’ll miss the most are those onstage moments when the theater became unhinged and my father led the audience and the other musicians on an out-of-body experience. There was a transition and then a resolution. If you didn’t know what visionary was, you just experienced it. Me, I’m totally spoiled. It’s probably why I never sought to join another band. How do you top that? (Not to mention that I was encouraged to play anything I wanted.)

After a concert, my father was on a high. Those hours, days, weeks, months of rehearsal, those hundreds of tunes, parts and revisions, had paid off. I think Pat Metheny may have heard about Ornette World, but even someone who tours as relentlessly as Pat didn’t know it would be twelve hours every day for weeks, and at 100 miles an hour, with no end in sight — and as the road got more open, the faster Dad went as we worked on the Song X album.

But that is how my father was wired. Very unassuming, very humble, very soft-spoken, but an absolute beast when it came to musicianship, knowledge, holding the world in his hand and knowing it. Others may have had no idea, but he knew he was an alchemist.

Aside from the shows, it’s the everyday laughing and eating I miss. Dad had a wicked sense of humor and a great talent for reading people. Traveling through airports was a riot. He loved to eat BBQ at Roger Hughes in Fort Worth, Thai food at a spot down behind the courthouse in New York’s Chinatown, and at La Coupole in Paris. If we landed in Italy early enough on the first day, we’d run out and find the local deli. Dad would buy mortadella, antipasti, and good bread, then head back to his room at the hotel to build huge and delicious sandwiches for all of us.

My father’s last public concert was at the London Jazz Festival in November 2011, a sold-out show at the Southbank Centre. A great night, one of those nights where he floated above and then took the audience with him. It reminded me of a night we had in Sao Paulo in 2010. It was the second night there, when towards the end of the set, the power went out in the theater. Complete darkness and silence in a theater of a couple of thousand people. Pitch black, and then after about a minute of stillness, my father began playing acoustically and we fell in behind him. The audience roared and we played in the dark for the next several minutes until the power came on. Now that was a surreal and an amazing moment.

We were supposed to tour the next year, but he just wasn’t feeling well, so we canceled the entire 2012 schedule. Dad was at home at the start of 2013, when he fell and broke his hip. The injury required no surgery, but he spent the whole year recovering. But it was another year when we did not go out on the road. So here comes 2014. In March we threw a big birthday party for him at his loft on West 36th Street as we did every year.

His loft was more like an art gallery with a bedroom and music studio attached. The paintings were by all different types of artists, including the Nigerian painters Z.K. Oloruntoba and Twins Seven Seven, a couple of his favorites. There were also works by Bob Thompson, Ed Clark, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns and many others.

He always liked living in large open spaces. In Soho when he had Artist House, on the third floor loft where he lived, he did the same thing. A gut renovation to have a large open space. The living room had a life raft instead of a couch, a hammock, and a pool table. In the back there was a full modern sauna.

At the 2014 party, it suddenly struck me that we might not be playing again — or at least that our days of hitting the road were over. This was Dad’s 84th birthday. It’s an age when physical things start to catch up with you. I said to myself, I ought to put together a tribute for my father right now. I wanted him to feel the love that was there for him. I did not want to wait the six months to a year it takes to organize a huge event. I felt an urgency.

I started looking for a substantial venue. There was only one available date. It was in early June at the “Celebrate Brooklyn” concert series in Prospect Park.

I began making calls to artists and the response was tremendous. If an artist was free on that date, he was coming. I managed to solidify the line-up in about two weeks. We announced in April that the concert would take place two months later.

When the night of the show arrived, we didn’t expect my dad to perform, but we brought his horn — that famous white saxophone — just in case. Backstage was just fantastic. All of the artists were so excited to be with my father. It was especially great to see him and Sonny Rollins just hanging out together. The two of them, always buddies, went way back. Sonny reminded me that In L.A. during the early 60’s the two of them would go out to the beach and play, bringing me along with them. On this occasion Sonny was dealing with his own health problems – he hadn’t performed much for quite a while. But he said, “I’m coming. I want to be there,” and he drove down from Woodstock where he lives, then made a beautiful speech to begin the concert. Eric Adams, the borough president, had declared it Ornette Coleman Day in Brooklyn. Backstage, he was so excited to meet Sonny.

When the show started, my father was sitting on the side of the stage. Onstage, we played the first two tunes of the night. Then they started waving to me from the wings: “He wants to come out and play.” So my son Ali, whose first name is also Ornette, walked his grandfather onstage and sat him in a chair, front and center. Henry Threadgill, David Murray and Flea were already onstage, along with Denardo Vibe, the house band: Al MacDowell, electric piccolo bass; Charlie Ellerbe, guitar; Tony Falanga, acoustic bass; Antoine Roney, tenor sax; and me on drums. We started playing “Turnaround.” It’s from a 1959 recording on Contemporary called Tomorrow is the Question. A slow blues, it still sounds great. We’d played it a lot as a quartet throughout the 2000’s: my father, Al, Tony, and me. Well, my father decides not to play on the tune. He sits with his horn, just listening and getting acclimated to being onstage again. It’s been almost three years.

All the musicians keep their eyes on Ornette, leaving room for him to start playing at any moment. When we finish “Turnaround,” my father picks up his horn and plays a phrase. The nearly 7,000 people crowded into the Prospect Park Bandshell that night all go wild. Then my father starts playing, solo. There is no mistaking my father’s sound. It’s like someone singing. Someone wailing. Skipping through the heavens or on a chain gang. A field holler as if sung by the singers he spoke about the most often, the opera singer Joan Sutherland and the Cantor Joseph Rosenblatt. Always telling a story.

The Vibe had spent the previous month rehearsing in the music room at Ornette’s place. The five of us and some of the musicians, Henry Threadgill, Joe Lovano, Geri Allen, Bill Laswell. We had prepared around 20 tunes for the concert. The other musicians had arrived from all over the map for a rehearsal the day before the show: Branford Marsalis from North Carolina, Bruce Hornsby from Virginia, David Murray from Paris, Ravi Coltrane in from a tour, and Flea from Los Angeles on his way to the Isle of Wight for a show with the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

I have decided to start this recording with Ornette’s two performances that night, “O.C. Turnaround,” and “Ramblin’.” Between making an unexpected speech to the audience and then performing, my father made an already historic night truly magical. With additional performances including Patti Smith and her great band, Savion Glover, Thurston Moore, Nels Cline, Laurie Anderson, John Zorn, and Master Musicians of Jajouka, the show elevated to the stratosphere. As Gregg Mann, Ornette’s long-time engineer and the night’s emcee, noted, “This was a once-in-a-lifetime show. It will never happen again.”

Even now, several months later, I still cannot write much about his passing. But I can say that the memorial service for him was extraordinary. It was a celebration, a concert, and a reflection of an enlightened person. My father breathed rare air that only few do. That’s why the giants are the giants.

The Master Musicians of Jajouka traveled from Morocco and led the procession into the church. Sonny Rollins was first in the line that formed behind the casket. Phil Schaap, the legendary NY radio host, officiated the afternoon. Phil Schaap began broadcasting an annual 24-hour Ornette Coleman birthday broadcast on WKCR in 1970 and has continued, this being the 46th straight year. Truly an inspirational person, Phil was the only person meant to host this gathering.

Pharoah Sanders, Ornette’s great friend from the 1960s, began the service with a solo performance. Cecil Taylor, who Ornette had just reunited with a few months earlier at the 2015 birthday party in March, where they talked into the wee hours, performed beautifully. The Jack DeJohnette-Savion Glover duet took the roof off the cathedral. Henry Threadgill wrote a piece, “Sail,” for this moment. He and Jason Moran brought so much spiritual harmony. Ravi Coltrane and Geri Allen played “Peace,” weaving together its beauty. The story that Phil Schapp told about John Coltrane and my father made everything stop, as people understood how the spirituality of these two beings was connected. David Murray, Joe Lovano, Al Macdowell, Charnett Moffett and I played “Lonely Woman.” It had a different meaning, this performance. The members of both Prime Time bands ended a full day of music: Bern Nix, Charlie Ellerbe, Jamaaladeen Tacuma, Dave Bryant, Chris Rosenberg and Ken Wessel. They are also sons of Ornette, as were so many musicians who were there in attendance.

One of the things that makes New York so essential, so hip, is the confluence of jazz, poets, writers, artists, all converging in an explosion of a scene that cannot be replicated. The presence of poets Felipe Luciano, Steve Dalachinsky, musician Karl Berger, sculptor Melvin Edwards and writers Howard Mandel, Herb Boyd, and Larry Blumenthal, added insight to Ornette as only a creative person can. What is Harmolodics? Can you parent Harmolodically? Football over music? They answered it.

And then came the Eulogy. What was already a day like none other was about to go through the roof. This was my favorite part of the day. It’s what turned good feelings into a Kool-Aid smile for everyone there. Bringing so much peace and joy to the congregation. The Reverend James A Forbes Jr., Senior Pastor of the Riverside Church, had a direct conversation with Ornette in his Eulogy. They spoke about the struggles of “trying to sing your song,” and “a dog around every corner.” Ending with his own song, and taking the Church on a journey, as Ornette did in his concerts.

Scholars and journalists and musicians will continue to debate the merits and impact of my father’s work. But make no mistake, he fully knew what he was doing. Ornette had it all worked out.

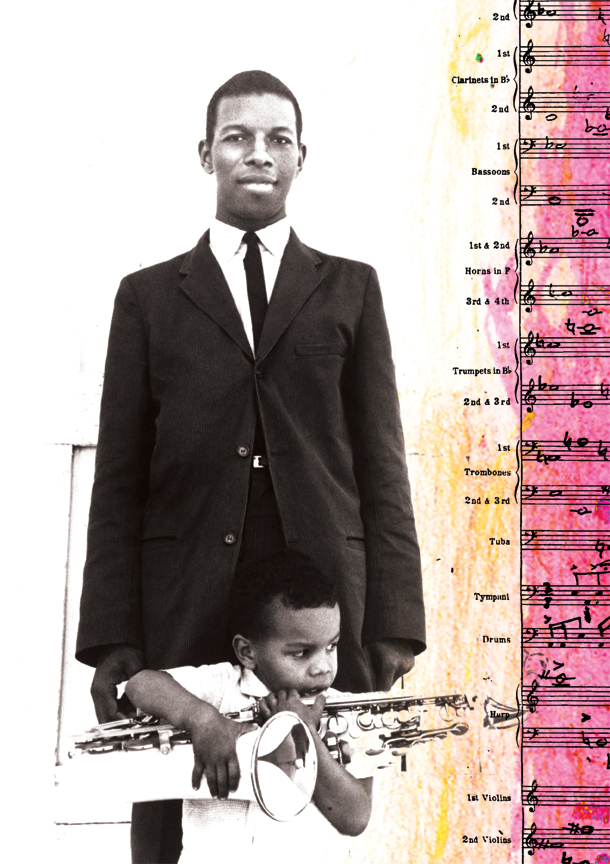

Denardo Coleman made his recording debut in 1966 as the drummer on his father’s album, “The Empty Foxhole.” He was ten years old at the time.